Overthrow Of The Hawaiian Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a ''

As early as 1873, a United States military commission recommended attempting to obtain

As early as 1873, a United States military commission recommended attempting to obtain

On January 20, 1887, the United States began leasing Pearl Harbor. Shortly afterwards, a group of mostly non-Hawaiians calling themselves the Hawaiian Patriotic League began the Rebellion of 1887. They drafted their own constitution on July 6, 1887. The new constitution was written by

On January 20, 1887, the United States began leasing Pearl Harbor. Shortly afterwards, a group of mostly non-Hawaiians calling themselves the Hawaiian Patriotic League began the Rebellion of 1887. They drafted their own constitution on July 6, 1887. The new constitution was written by

The Wilcox Rebellion of 1888 was a plot to overthrow King David Kalākaua, king of Hawaii, and replace him with his sister in a

The Wilcox Rebellion of 1888 was a plot to overthrow King David Kalākaua, king of Hawaii, and replace him with his sister in a

In November 1889, Kalākaua traveled to San Francisco for his health, staying at the Palace Hotel. He died there on January 20, 1891. His sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne in the middle of an economic crisis. The

In November 1889, Kalākaua traveled to San Francisco for his health, staying at the Palace Hotel. He died there on January 20, 1891. His sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne in the middle of an economic crisis. The

The events began on January 17, 1893, when John Good, a revolutionist, shot Leialoha, a native policeman who was trying to stop a wagon carrying weapons to the Committee of Safety led by Lorrin Thurston. The Committee of Safety feared the shooting would bring government forces to rout out the conspirators and stop the overthrow before it could begin. The Committee of Safety initiated the overthrow by organizing armed non-native men, under their leadership, intending to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The forces garrisoned Ali'iolani Hale across the street from

The events began on January 17, 1893, when John Good, a revolutionist, shot Leialoha, a native policeman who was trying to stop a wagon carrying weapons to the Committee of Safety led by Lorrin Thurston. The Committee of Safety feared the shooting would bring government forces to rout out the conspirators and stop the overthrow before it could begin. The Committee of Safety initiated the overthrow by organizing armed non-native men, under their leadership, intending to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The forces garrisoned Ali'iolani Hale across the street from

President Harrison's Secretary of State John W. Foster in 1892–1894 actively worked for the annexation of the independent Republic of Hawaii. Pro-American business interests had overthrown the Queen when she rejected constitutional limits on her powers. The new government realized that Hawaii was too small and militarily weak to survive in a world of aggressive imperialism, especially on the part of Japan. It was eager for American annexation. Foster believed Hawaii was vital to American interests in the Pacific.

The annexation program was coordinated by the chief American diplomat on the scene,

President Harrison's Secretary of State John W. Foster in 1892–1894 actively worked for the annexation of the independent Republic of Hawaii. Pro-American business interests had overthrown the Queen when she rejected constitutional limits on her powers. The new government realized that Hawaii was too small and militarily weak to survive in a world of aggressive imperialism, especially on the part of Japan. It was eager for American annexation. Foster believed Hawaii was vital to American interests in the Pacific.

The annexation program was coordinated by the chief American diplomat on the scene,

A provisional government was set up with the strong support of the

A provisional government was set up with the strong support of the

The Committee of Safety declared Sanford Dole President of the new Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawai'i on January 17, 1893, only removing the queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawai'i was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the government's intention to campaign for Hawaii's annexation to the United States. The rationale behind the annexation of Hawaii included a strong economic component—Hawaiian goods and services which were exported to the mainland would not be subjected to United States tariffs, and the United States and Hawaii would both benefit from each other's domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States.

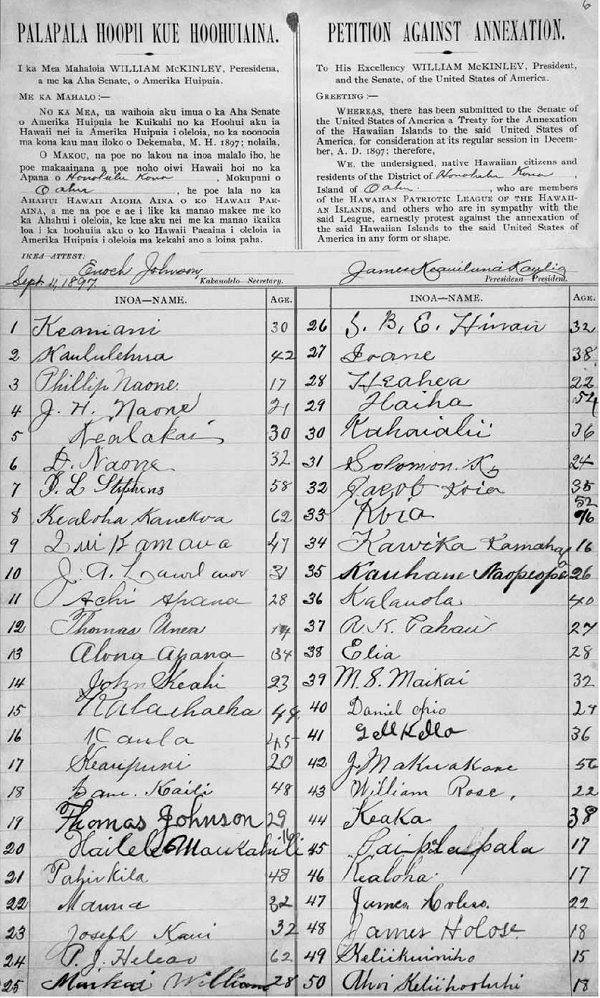

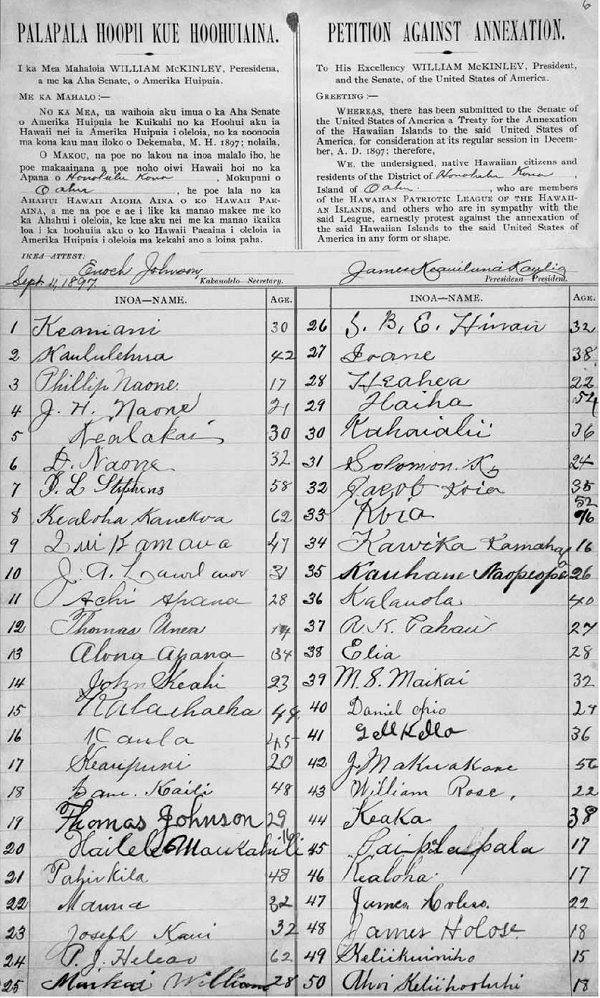

In 1897,

The Committee of Safety declared Sanford Dole President of the new Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawai'i on January 17, 1893, only removing the queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawai'i was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the government's intention to campaign for Hawaii's annexation to the United States. The rationale behind the annexation of Hawaii included a strong economic component—Hawaiian goods and services which were exported to the mainland would not be subjected to United States tariffs, and the United States and Hawaii would both benefit from each other's domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States.

In 1897,

morganreport.org

Online images and transcriptions of the entire 1894 Morgan Report * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawaiian Kingdom, Overthrow Of the United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries Coups d'état and coup attempts in the United States 1890s coups d'état and coup attempts 1893 in Hawaii Conflicts in 1893 Battles and conflicts without fatalities January 1893 events United States involvement in regime change

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' against Queen Liliʻuokalani

Liliʻuokalani (; Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha; September 2, 1838 – November 11, 1917) was the only queen regnant and the last sovereign monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, ruling from January 29, 1891, until the overthrow of the Haw ...

, which took place on January 17, 1893, on the island of Oahu

Oahu () (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering place#Island of Oʻahu as The Gathering Place, Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over t ...

and led by the Committee of Safety, composed of seven foreign residents and six non-aboriginal Hawaiian Kingdom

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the ...

subjects of American descent in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

. The Committee prevailed upon American minister John L. Stevens

John Leavitt Stevens (August 1, 1820 – February 8, 1895) was the United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 when he was accused of conspiring to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani in association with the Committee of Safety, led by ...

to call in the U.S. Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the Marines, maritime land force military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary warfare, exped ...

to protect the national interest

The national interest is a sovereign state's goals and ambitions (economic, military, cultural, or otherwise), taken to be the aim of government.

Etymology

The Italian phrase ''ragione degli stati'' was first used by Giovanni della Casa around t ...

of the United States of America. The insurgents established the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii ( Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'') was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had ended, and August 12, 1898, when it became annexed by the United State ...

, but their ultimate goal was the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the islands to the United States, which occurred in 1898.

The 1993 Apology Resolution

United States Public Law 103-150, informally known as the Apology Resolution, is a Joint Resolution of the U.S. Congress adopted in 1993 that "acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of age ...

by the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

concedes that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and ..the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum". Debates regarding the event play an important role in the Hawaiian sovereignty movement

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement ( haw, ke ea Hawaiʻi), is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to re-establish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii due to desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-gove ...

.

Background

The Kamehameha Dynasty was the reigning monarchy of the Hawaiian Kingdom, beginning with its founding byKamehameha I

Kamehameha I (; Kalani Paiea Wohi o Kaleikini Kealiikui Kamehameha o Iolani i Kaiwikapu kaui Ka Liholiho Kūnuiākea; – May 8 or 14, 1819), also known as Kamehameha the Great, was the conqueror and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii. T ...

in 1795, until the death of Kamehameha V

Kamehameha V (Lota Kapuāiwa Kalanimakua Aliʻiōlani Kalanikupuapaʻīkalaninui; December 11, 1830 – December 11, 1872), reigned as the fifth monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaiʻi from 1863 to 1872. His motto was "Onipaʻa": i ...

in 1872 and Lunalilo

Lunalilo (William Charles Lunalilo; January 31, 1835 – February 3, 1874) was the sixth monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii from his election on January 8, 1873, until his death a year later.

Born to Kekāuluohi and High Chief Charles Kanaʻina, ...

in 1874. On July 6, 1846, U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

John C. Calhoun, on behalf of President Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

, formally recognized Hawaii's independence under the reign of Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 – December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name is Keaweaweula Kīwalaō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K� ...

. As a result of the recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into treaties with the major nations of the world and established over ninety legations and consulates in multiple seaports and cities. The kingdom would continue for another 21 years until its overthrow in 1893 with the fall of the House of Kalākaua

The House of Kalākaua, or Kalākaua Dynasty, also known as the Keawe-a-Heulu line, was the reigning family of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi between the assumption of King David Kalākaua to the throne in 1874 and the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokala ...

.

Sugar reciprocity

Sugar had been a major export from Hawaii since CaptainJames Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

arrived in 1778. The first permanent plantation in the islands was on Kauai

Kauai, () anglicized as Kauai ( ), is geologically the second-oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands (after Niʻihau). With an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), it is the fourth-largest of these islands and the 21st largest island ...

in 1835. William Hooper

William Hooper (June 28, 1742 October 14, 1790) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, and politician. As a member of the Continental Congress representing North Carolina, Hooper signed the Continental Association and the Declaration of ...

leased 980 acres (4 km²) of land from Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 – December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name is Keaweaweula Kīwalaō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K� ...

and began growing sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalks t ...

. Within thirty years there would be plantations on four of the main islands. Sugar had completely altered Hawaii's economy.

The influence of the United States in Hawaiian government began with American-born plantation owners advocating for fair representation in the Kingdom's politics, owing to the significant tax contributions made from the plantations to both the Royal family and national economy. This was driven by missionary religion and the economics of the sugar industry

The sugar industry subsumes the production, processing and marketing of sugars (mostly sucrose and fructose). Globally, most sugar is extracted from sugar cane (~80% predominantly in the tropics) and sugar beet (~ 20%, mostly in temperate cli ...

. Pressure from these foreign-born politicians was being felt by the King and chiefs with demands of land tenure. The 1839 Hawaiian Bill of Rights, also known as the 1839 Constitution of Hawaii, was an attempt by Kamehameha III and his chiefs to guarantee that the Hawaiian people would not lose their tenured land, and provided the groundwork for a free enterprise

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ...

system. After a five-month occupation by George Paulet in 1843, Kamehameha III relented to the foreign advisors to private land demands with the Great Māhele

The Great Māhele ("to divide or portion") or just the Māhele was the Hawaiian land redistribution proposed by King Kamehameha III. The Māhele was one of the most important episodes of Hawaiian history, second only to the overthrow of the Hawa ...

, distributing the lands as pushed on heavily by the missionaries, including Gerrit P. Judd

Gerrit Parmele Judd (April 23, 1803 – July 12, 1873) was an American physician and missionary to the Kingdom of Hawaii who later renounced his American citizenship and became a trusted advisor and cabinet minister to King Kamehameha III.

He ...

. During the 1850s, the U.S. import tariff on sugar from Hawaii was much higher than the import tariffs Hawaiians were charging the U.S., and Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 – December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name is Keaweaweula Kīwalaō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K� ...

sought reciprocity. The monarch wished to lower the tariffs being paid out to the U.S. while still maintaining the Kingdom's sovereignty and making Hawaiian sugar competitive with other foreign markets. In 1854 Kamehameha III proposed a policy of reciprocity between the countries but the proposal died in the U.S. Senate.>

As early as 1873, a United States military commission recommended attempting to obtain

As early as 1873, a United States military commission recommended attempting to obtain Ford Island

Ford Island ( haw, Poka Ailana) is an islet in the center of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It has been known as Rabbit Island, Marín's Island, and Little Goats Island, and its native Hawaiian name is ''Mokuumeume''. The isl ...

in exchange for the tax-free importation of sugar to the U.S. Major General John Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later served ...

, U.S. commander of the military division of the Pacific, and Brevet Brigadier General Burton S. Alexander arrived in Hawaii to ascertain its defensive capabilities. United States control of Hawaii was considered vital for the defense of the west coast of the United States, and they were especially interested in Pu'uloa, Pearl Harbor. The sale of one of Hawaii's harbors was proposed by Charles Reed Bishop

Charles Reed Bishop (January 25, 1822 – June 7, 1915) was an American businessman, politician, and philanthropist in Hawaii. Born in Glens Falls, New York, Glens Falls, New York (state), New York, he sailed to Hawaii in 1846 at the age of 24, a ...

, a foreigner who had married into the Kamehameha family, had risen in the government to be Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, and owned a country home near Pu'uloa. He showed the two U.S. officers around the lochs, although his wife, Bernice Pauahi Bishop

Bernice Pauahi Bishop KGCOK RoK (December 19, 1831 – October 16, 1884), born Bernice Pauahi Pākī, was an '' alii'' (noble) of the Royal Family of the Kingdom of Hawaii and a well known philanthropist. At her death, her estate was the la ...

, privately disapproved of selling Hawaiian lands. As monarch, William Charles Lunalilo

Lunalilo (William Charles Lunalilo; January 31, 1835 – February 3, 1874) was the sixth monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaii from his election on January 8, 1873, until his death a year later.

Born to Kekāuluohi and Charles Kana� ...

, was content to let Bishop run almost all business affairs but the ceding of lands would become unpopular with the native Hawaiians. Many islanders thought that all the islands, rather than just Pearl Harbor, might be lost and opposed any cession of land. By November 1873, Lunalilo canceled negotiations and returned to drinking, against his doctor's advice; his health declined swiftly, and he died on February 3, 1874.

Lunalilo left no heirs. The legislature was empowered by the constitution to elect the monarch in these instances and chose David Kalākaua

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

as the next monarch. The new ruler was pressured by the U.S. government to surrender Pearl Harbor to the Navy. Kalākaua was concerned that this would lead to annexation by the U.S. and to the contravention of the traditions of the Hawaiian people, who believed that the land ('Āina) was fertile, sacred, and not for sale to anyone. In 1874 through 1875, Kalākaua traveled to the United States for a state visit to Washington, DC to help gain support for a new treaty. Congress agreed to the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875

The Treaty of reciprocity between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom ( Hawaiian: ''Kuʻikahi Pānaʻi Like'') was a free trade agreement signed and ratified in 1875 that is generally known as the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875.

T ...

for seven years in exchange for Ford Island. After the treaty, sugar production expanded from of farm land to in 1891. At the end of the seven-year reciprocity agreement, the United States showed little interest in renewal.

Rebellion of 1887 and the Bayonet Constitution

On January 20, 1887, the United States began leasing Pearl Harbor. Shortly afterwards, a group of mostly non-Hawaiians calling themselves the Hawaiian Patriotic League began the Rebellion of 1887. They drafted their own constitution on July 6, 1887. The new constitution was written by

On January 20, 1887, the United States began leasing Pearl Harbor. Shortly afterwards, a group of mostly non-Hawaiians calling themselves the Hawaiian Patriotic League began the Rebellion of 1887. They drafted their own constitution on July 6, 1887. The new constitution was written by Lorrin Thurston

Lorrin Andrews Thurston (July 31, 1858 – May 11, 1931) was an American lawyer, politician, and businessman born and raised in the Kingdom of Hawaii. Thurston played a prominent role in the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom that replaced Q ...

, the Hawaiian Minister of the Interior who used the Hawaiian militia as threat against Kalākaua. Kalākaua was forced under threat of assassination to dismiss his cabinet ministers and sign a new constitution which greatly lessened his power. It would become known as the "Bayonet Constitution

The 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a legal document prepared by anti-monarchists to strip the Hawaiian monarchy of much of its authority, initiating a transfer of power to American, European and native Hawaiian elites. It became k ...

" because of the threat of force used.

The Bayonet Constitution allowed the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but had stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.} Eligibility to vote for the House of Nobles was also altered, stipulating that both candidates and voters were now required to own property valuing at least three thousand dollars, or have an annual income of no less than six hundred dollars. This resulted in disenfranchising two-thirds of the native Hawaiians as well as other ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

s who had previously held the right to vote but were no longer able to meet the new voting requirements. This new constitution benefited the white, foreign plantation owners. With the legislature now responsible for naturalizing citizens, Americans and Europeans could retain their home country citizenship and vote as citizens of the kingdom. Along with voting privileges, Americans could now run for office and still retain their United States citizenship, something not afforded in any other nation of the world and even allowed Americans to vote without becoming naturalized Asian immigrants were completely shut out and were no longer able to acquire citizenship or vote at all.

At the time of the Bayonet Constitution Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

was president, and his secretary of state Thomas F. Bayard

Thomas Francis Bayard (October 29, 1828 – September 28, 1898) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat from Wilmington, Delaware. A Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, he served three terms as United States Senate, United States ...

sent written instructions to the American minister George W. Merrill that in the event of another revolution in Hawaii, it was a priority to protect American commerce, lives and property. Bayard specified, "the assistance of the officers of our Government vessels, if found necessary, will therefore be promptly afforded to promote the reign of law and respect for orderly government in Hawaii." In July 1889, there was a small scale rebellion, and Minister Merrill landed Marines to protect Americans; the State Department explicitly approved his action. Merrill's replacement, minister John L. Stevens

John Leavitt Stevens (August 1, 1820 – February 8, 1895) was the United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 when he was accused of conspiring to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani in association with the Committee of Safety, led by ...

, read those official instructions, and followed them in his controversial actions of 1893.

Wilcox Rebellion of 1888

The Wilcox Rebellion of 1888 was a plot to overthrow King David Kalākaua, king of Hawaii, and replace him with his sister in a

The Wilcox Rebellion of 1888 was a plot to overthrow King David Kalākaua, king of Hawaii, and replace him with his sister in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

in response to increased political tension between the legislature and the king after the 1887 constitution. Kalākaua's sister, Princess Liliʻuokalani and his wife, Queen Kapiolani

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mothe ...

, returned from Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee

The Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated on 20 and 21 June 1887 to mark the 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession on 20 June 1837. It was celebrated with a Thanksgiving Service at Westminster Abbey, and a banquet to which ...

immediately after news reached them in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

.

In October 1887, Robert William Wilcox

Robert William Kalanihiapo Wilcox (February 15, 1855 – October 23, 1903), nicknamed the Iron Duke of Hawaii, was a Native Hawaiian whose father was an American and whose mother was Hawaiian. A revolutionary soldier and politician, he led uprisi ...

, a native Hawaiian officer and veteran of the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, returned to Hawaii. The funding had stopped for his study program when the new constitution was signed. Wilcox, Charles B. Wilson

Charles Burnett "C.B." Wilson (4 July 1850 – 12 September 1926) was a British and Tahitian superintendent of the water works, fire chief under Kalākaua, King Kalākaua, and Marshal of the Kingdom under Liliuokalani, Queen Liliuokalani. Wilson w ...

, Princess Liliʻuokalani, and Samuel Nowlein

Samuel Nowlein (April 3, 1851 – December 5, 1905) was a Native Hawaiian Colonel who was a monarchist and known for organizing the 1895 Wilcox rebellion against the Republic of Hawaii before being caught and arrested during the rebellion.

Biogr ...

plotted to overthrow King Kalākaua to replace him with his sister, Liliʻuokalani. They had 300 Hawaiian conspirators hidden in ʻIolani Barracks

Iolani Barracks, or ''hale koa'' (house fwarriors); in Hawaiian, was built in 1870, designed by the architect Theodore Heuck, under the direction of King Lot Kapuaiwa. Located directly adjacent to Iolani Palace in downtown Honolulu, it housed ab ...

and an alliance with the Royal Guard, but the plot was accidentally discovered in January 1888, less than 48 hours before the revolt would have been initiated. No one was prosecuted but Wilcox was exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

d. So on February 11, 1888, Wilcox left Hawaii for San Francisco, intending to return to Italy with his wife.

Princess Liliʻuokalani was offered the throne several times by the Missionary Party

The Reform Party, also referred to as "the Missionary Party", or the "Down-Town Party", was a political party in the Kingdom of Hawaii. It was founded by descendants of Protestant missionaries that came to Hawaii from New England. Following the Ann ...

who had forced the Bayonet Constitution on her brother, but she believed she would become a powerless figurehead like her brother and rejected the offers outright.

Liliʻuokalani attempts to re-write Constitution

In November 1889, Kalākaua traveled to San Francisco for his health, staying at the Palace Hotel. He died there on January 20, 1891. His sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne in the middle of an economic crisis. The

In November 1889, Kalākaua traveled to San Francisco for his health, staying at the Palace Hotel. He died there on January 20, 1891. His sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne in the middle of an economic crisis. The McKinley Act

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

had crippled the Hawaiian sugar industry by removing the duties on sugar imports from other countries into the US, eliminating the previous Hawaiian advantage gained via the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875. Many Hawaii businesses and citizens felt pressure from the loss of revenue; in response Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery

A lottery is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find some degree of ...

system to raise money for her government. Also proposed was a controversial opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

licensing bill. Her ministers, and closest friends, were all opposed to this plan; they unsuccessfully tried to dissuade her from pursuing these initiatives, both of which came to be used against her in the brewing constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani's chief desire was to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Bayonet Constitution and promulgating a new one, an idea that seems to have been broadly supported by the Hawaiian population. The 1893 Constitution would have increased suffrage by reducing some property requirements, and eliminated the voting privileges extended to European and American residents. It would have disenfranchised many resident European and American businessmen who were not citizens of Hawaii. The Queen toured several of the islands on horseback, talking to the people about her ideas and receiving overwhelming support, including a lengthy petition in support of a new constitution. However, when the Queen informed her cabinet of her plans, they withheld their support due to an understanding of what her opponents' likely response to these plans would be.

Though there were threats to Hawaii's sovereignty throughout the Kingdom's history, it was not until the signing of the Bayonet Constitution in 1887 that this threat began to be realized. The precipitating event leading to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, was the attempt by Queen Liliʻuokalani to promulgate a new constitution that would have strengthened the power of the monarch relative to the legislature, where Euro-American business elites held disproportionate power. The stated goals of the conspirators, who were non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects (five United States nationals, one English national, and one German national) were to depose the queen, overthrow the monarchy, and seek Hawaii's annexation to the United States.

1893 Hawaiian coup d'état and overthrow of the kingdom

The overthrow of the monarchy was started by newspaper publisher Lorrin Thurston, a Hawaiian subject and former Minister of the Interior who was the grandson of American missionaries, and formally led by the Chairman of the Committee of Safety,Henry E. Cooper

Henry Ernest Cooper (August 28, 1857 – May 15, 1929) was an American people, American lawyer who moved to the Kingdom of Hawaii and became prominent in Hawaiian politics in the 1890s. He formally deposed Queen Lili'uokalani of Hawaii in 1893, h ...

, an American lawyer. They derived their support primarily from the American and European business class residing in Hawaii and other supporters of the Reform Party of the Hawaiian Kingdom

The Reform Party, also referred to as "the Missionary Party", or the "Down-Town Party", was a political party in the Kingdom of Hawaii. It was founded by descendants of Protestant missionaries that came to Hawaii from New England. Following the Ann ...

. Most of the leaders of the Committee of Safety that deposed the queen were United States and European citizens who were also Kingdom subjects. They included legislators, government officers, and a Supreme Court Justice of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On January 16, the Marshal of the Kingdom, Charles B. Wilson

Charles Burnett "C.B." Wilson (4 July 1850 – 12 September 1926) was a British and Tahitian superintendent of the water works, fire chief under Kalākaua, King Kalākaua, and Marshal of the Kingdom under Liliuokalani, Queen Liliuokalani. Wilson w ...

, was tipped off by detectives to the imminent planned overthrow. Wilson requested warrants

Warrant may refer to:

* Warrant (law), a form of specific authorization

** Arrest warrant, authorizing the arrest and detention of an individual

** Search warrant, a court order issued that authorizes law enforcement to conduct a search for eviden ...

to arrest the 13-member council of the Committee of Safety, and put the Kingdom under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. Because the members had strong political ties with United States Government Minister John L. Stevens

John Leavitt Stevens (August 1, 1820 – February 8, 1895) was the United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 when he was accused of conspiring to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani in association with the Committee of Safety, led by ...

, the requests were repeatedly denied by Attorney General Arthur P. Peterson and the Queen's cabinet, fearing if approved, the arrests would escalate the situation. After a failed negotiation with Thurston, Wilson began to collect his men for the confrontation. Wilson and Captain of the Royal Household Guard, Samuel Nowlein

Samuel Nowlein (April 3, 1851 – December 5, 1905) was a Native Hawaiian Colonel who was a monarchist and known for organizing the 1895 Wilcox rebellion against the Republic of Hawaii before being caught and arrested during the rebellion.

Biogr ...

, had rallied a force of 496 men who were kept at hand to protect the Queen.

The events began on January 17, 1893, when John Good, a revolutionist, shot Leialoha, a native policeman who was trying to stop a wagon carrying weapons to the Committee of Safety led by Lorrin Thurston. The Committee of Safety feared the shooting would bring government forces to rout out the conspirators and stop the overthrow before it could begin. The Committee of Safety initiated the overthrow by organizing armed non-native men, under their leadership, intending to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The forces garrisoned Ali'iolani Hale across the street from

The events began on January 17, 1893, when John Good, a revolutionist, shot Leialoha, a native policeman who was trying to stop a wagon carrying weapons to the Committee of Safety led by Lorrin Thurston. The Committee of Safety feared the shooting would bring government forces to rout out the conspirators and stop the overthrow before it could begin. The Committee of Safety initiated the overthrow by organizing armed non-native men, under their leadership, intending to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The forces garrisoned Ali'iolani Hale across the street from ʻIolani Palace

The Iolani Palace ( haw, Hale Aliʻi ʻIolani) was the royal residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaii beginning with Kamehameha III under the Kamehameha Dynasty (1845) and ending with Queen Liliʻuokalani (1893) under the Kalākaua Dyna ...

and waited for the Queen's response.

As these events were unfolding, the Committee of Safety expressed concern for the safety and property of American residents in Honolulu.

On January 17, 1893, the Chairman of the Committee of Safety, Henry E. Cooper

Henry Ernest Cooper (August 28, 1857 – May 15, 1929) was an American people, American lawyer who moved to the Kingdom of Hawaii and became prominent in Hawaiian politics in the 1890s. He formally deposed Queen Lili'uokalani of Hawaii in 1893, h ...

, addressed a crowd assembled in front of ʻIolani Palace

The Iolani Palace ( haw, Hale Aliʻi ʻIolani) was the royal residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaii beginning with Kamehameha III under the Kamehameha Dynasty (1845) and ending with Queen Liliʻuokalani (1893) under the Kalākaua Dyna ...

(the official royal residence) and read aloud a proclamation that formally deposed Queen Liliʻuokalani, abolished the Hawaiian monarchy

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the ...

, and established a Provisional Government of Hawaii

The Provisional Government of Hawaii (abbr.: P.G.; Hawaiian: ''Aupuni Kūikawā o Hawaiʻi'') was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety under the leadership of its ch ...

under President Sanford B. Dole

Sanford Ballard Dole (April 23, 1844 – June 9, 1926) was a lawyer and jurist from the Hawaiian Islands. He lived through the periods when Hawaii was a kingdom, protectorate, republic, and territory. A descendant of the American missionary ...

.

United States involvement

President Harrison's Secretary of State John W. Foster in 1892–1894 actively worked for the annexation of the independent Republic of Hawaii. Pro-American business interests had overthrown the Queen when she rejected constitutional limits on her powers. The new government realized that Hawaii was too small and militarily weak to survive in a world of aggressive imperialism, especially on the part of Japan. It was eager for American annexation. Foster believed Hawaii was vital to American interests in the Pacific.

The annexation program was coordinated by the chief American diplomat on the scene,

President Harrison's Secretary of State John W. Foster in 1892–1894 actively worked for the annexation of the independent Republic of Hawaii. Pro-American business interests had overthrown the Queen when she rejected constitutional limits on her powers. The new government realized that Hawaii was too small and militarily weak to survive in a world of aggressive imperialism, especially on the part of Japan. It was eager for American annexation. Foster believed Hawaii was vital to American interests in the Pacific.

The annexation program was coordinated by the chief American diplomat on the scene, John L. Stevens

John Leavitt Stevens (August 1, 1820 – February 8, 1895) was the United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 when he was accused of conspiring to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani in association with the Committee of Safety, led by ...

. He decided to send in a U.S. military detachment after the Queen was deposed to support the new government and prevent a vacuum that might open the way for Japan. Advised about supposed threats to non-combatant American lives and property by the Committee of Safety, Stevens obliged their request and summoned 162 U.S. sailors

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship.

The profession of the s ...

and Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

from the USS ''Boston'' to land on Oahu under orders of neutrality and take up positions at the U.S. Legation, Consulate, and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893.

The deposed Queen was kept in ʻIolani Palace under house arrest. The American sailors and Marines did not enter the Palace grounds or take over any buildings, and never fired a shot, but their presence served effectively. The Queen never had an army, the local police did not support her, and no one mobilized any pro-royalist forces. Historian William Russ states, "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself." Due to the Queen's desire "to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life" for her subjects and after some deliberation, at the urging of advisers and friends, the Queen ordered her forces to surrender. The Honolulu Rifles took over government buildings, disarmed the Royal Guard, and declared a provisional government.

According to the ''Queen's Book'', her friend and minister J.S. Walker "came and told me that he had come on a painful duty, that the opposition party had requested that I should abdicate." After consulting with her ministers, including Walker, the Queen concluded that "since the troops of the United States had been landed to support the revolutionists, by the order of the American minister, it would be impossible for us to make any resistance." Despite repeated claims that the overthrow was "bloodless", the ''Queen's Book'' notes that Liliʻuokalani received "friends hoexpressed their sympathy in person; amongst these Mrs. J. S. Walker, who had lost her husband by the treatment he received from the hands of the insurgents. He was one of many who from persecution had succumbed to death."

Immediate annexation was prevented by President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

who told Congress:

... the military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war; unless made either with the consent of the government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the government of the queen ... the existing government, instead of requesting the presence of an armed force, protested against it. There is as little basis for the pretense that forces were landed for the security of American life and property. If so, they would have been stationed in the vicinity of such property and so as to protect it, instead of at a distance and so as to command the Hawaiian Government Building and palace ... When these armed men were landed, the city of Honolulu was in its customary orderly and peaceful condition ...The Republic of Hawaii was nonetheless declared in 1894 by the same parties which had established the

provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

. Among them was Lorrin A. Thurston, a drafter of the Bayonet Constitution. The Committee of Safety asked Sanford Dole to become President of the forcibly instated Republic. He agreed, and became President on July 4, 1894.

Aftermath

A provisional government was set up with the strong support of the

A provisional government was set up with the strong support of the Honolulu Rifles

The Honolulu Rifles were the name of two volunteer military companies of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

First company

In 1857, the First Hawaiian Cavalry, an artillery and infantry company which was originally established in 1852, was renamed the Honolulu ...

, a militia group which had defended the system of government promulgated by the Bayonet Constitution against the Wilcox rebellion of 1889.

The Queen's statement yielding authority, on January 17, 1893, protested against the overthrow:

On December 19, 1898, the queen would amend the declaration with the ''"Memorial of Queen Liliuokalani in relation to the Crown lands of Hawaii"'', further protesting the overthrow and loss of property.

Response

United States

Newly inaugurated PresidentGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

called for an investigation into the overthrow. This investigation was conducted by former Congressman James Henderson Blount

James Henderson Blount (September 12, 1837 – March 8, 1903) was an American statesman, soldier and congressman from Georgia. He opposed the annexation of Hawaii in 1893 in his investigation into the American involvement in the political revolut ...

. Blount concluded in his report

A report is a document that presents information in an organized format for a specific audience and purpose. Although summaries of reports may be delivered orally, complete reports are almost always in the form of written documents. Usage

In ...

on July 17, 1893, "United States diplomatic and military representatives had abused their authority and were responsible for the change in government." Minister Stevens was recalled, and the military commander of forces in Hawaiʻi was forced to resign his commission. President Cleveland stated, "Substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair the monarchy." Cleveland further stated in his 1893 State of the Union Address that, "Upon the facts developed it seemed to me the only honorable course for our Government to pursue was to undo the wrong that had been done by those representing us and to restore as far as practicable the status existing at the time of our forcible intervention." The matter was referred by Cleveland to Congress on December 18, 1893, after the Queen refused to accept amnesty for the traitors as a condition of reinstatement. Hawaii President Sanford Dole was presented a demand for reinstatement by Minister Willis, who had not realized Cleveland had already sent the matter to Congress—Dole flatly refused Cleveland's demands to reinstate the Queen.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Senator John Tyler Morgan

John Tyler Morgan (June 20, 1824 – June 11, 1907) was an American politician was served as a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War and later was elected for six terms as the U.S. Senator (1877–1907) ...

(D-Alabama) and composed mostly of senators in favor of annexation, initiated their own investigation to discredit Blount's earlier report, using pro-annexationist affidavits from Hawaii, and testimony provided to the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The Morgan Report

The Morgan Report was an 1894 report concluding an official U.S. Congressional investigation into the events surrounding the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, including the alleged role of U.S. military troops (both bluejackets and marines) in the ...

contradicted the Blount Report, and exonerated Minister Stevens and the U.S. military troops finding them "not guilty" of involvement in the overthrow. Cleveland became stalled with his earlier efforts to restore the queen, and adopted a position of recognition of the so-called Provisional Government and the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii ( Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'') was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had ended, and August 12, 1898, when it became annexed by the United State ...

which followed.

The Native Hawaiian Study Commission of the United States Congress in its 1983 final report found no historical, legal, or moral obligation for the U.S. government to provide reparations, assistance, or group rights to Native Hawaiians.

In 1993, the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Congress passed a resolution, which President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

signed into law, offering an apology to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the United States for its involvement in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The law is known as the Apology Resolution

United States Public Law 103-150, informally known as the Apology Resolution, is a Joint Resolution of the U.S. Congress adopted in 1993 that "acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of age ...

, and represents one of the few times that the United States government has formally apologized for its actions.

International

Every government with a diplomatic presence in Hawaii, except for the United Kingdom, recognized the Provisional Government within 48 hours of the overthrow via their consulates. Countries recognizing the new Provisional Government included Chile, Austria-Hungary, Mexico, Russia, the Netherlands, Imperial Germany, Sweden, Spain, Imperial Japan, Italy, Portugal, Denmark, Belgium, China, Peru, and France. When the Republic of Hawaii was declared on July 4, 1894, immediate de facto recognition was given by every nation with diplomatic relations with Hawaii, except for Britain, whose response came in November 1894.Hawaiian counter-revolution

A four-day uprising between January 6–9, 1895, began with an attempted coup d'état to restore the monarchy, and included battles between royalists and the republican rebels. Later, after a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds after the attempted rebellion in 1895, Queen Lili'uokalani was placed under arrest, tried by a military tribunal of the Republic of Hawai'i, convicted ofmisprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

and imprisoned in her own home. On January 24, Lili'uokalani abdicated, formally ending the Hawaiian monarchy

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the ...

.

Republic, United States annexation, United States Territory

The Committee of Safety declared Sanford Dole President of the new Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawai'i on January 17, 1893, only removing the queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawai'i was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the government's intention to campaign for Hawaii's annexation to the United States. The rationale behind the annexation of Hawaii included a strong economic component—Hawaiian goods and services which were exported to the mainland would not be subjected to United States tariffs, and the United States and Hawaii would both benefit from each other's domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States.

In 1897,

The Committee of Safety declared Sanford Dole President of the new Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawai'i on January 17, 1893, only removing the queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawai'i was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the government's intention to campaign for Hawaii's annexation to the United States. The rationale behind the annexation of Hawaii included a strong economic component—Hawaiian goods and services which were exported to the mainland would not be subjected to United States tariffs, and the United States and Hawaii would both benefit from each other's domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States.

In 1897, William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

succeeded Cleveland as United States president. In his first year in office, the U.S. Senate failed twice to ratify a Treaty to Annex the Hawaiian Islands. A year later, he signed the Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution was a joint resolution passed on July 7, 1898, by the United States Congress to annex the independent Republic of Hawaii. In 1900, Congress created the Territory of Hawaii.

The resolution was drafted by Representative Fra ...

, which stated that the annexation of Hawaii would occur on July 7, 1898. The formal ceremony which marked the annexation of Hawaii to the United States was held at the Iolani Palace on August 12, 1898. Almost no Native Hawaiians attended the annexation ceremony, and those few Hawaiians who were on the streets wore royalist ilima blossoms in their hats or hair, and on their breasts, they wore Hawaiian flags which were emblazoned with the motto: ''Kuu Hae Aloha'' ('my beloved flag'). Most of the 40,000 Native Hawaiians, including Lili'uokalani and the Hawaiian royal family, protested against the illegal action by shuttering themselves in their homes. "When the news of the Annexation came, it was bitterer than death to me", Lili'uokalani's niece, Princess Kaʻiulani

Kaʻiulani (; Victoria Kawēkiu Kaʻiulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn; October 16, 1875 – March 6, 1899) was the only child of Princess Miriam Likelike, and the last heir apparent to the throne of the Hawaiian Kingdom. ...

, told the ''San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and M. H. de Young, Michael H. de ...

''. "It was bad enough to lose the throne, but it was infinitely worse to have the flag go down." The Hawaiian flag was lowered for the last time while the Royal Hawaiian Band

The Royal Hawaiian Band is the oldest and only full-time municipal band in the United States. At present a body of the City & County of Honolulu, the Royal Hawaiian Band has been entertaining Honolulu residents and visitors since its inception i ...

played the Hawaiian national anthem, ''Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī

"Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī" is the regional anthem of the U.S. state of Hawaii. It previously served as the national anthem of the independent Hawaiian Kingdom during the late 19th century, and has continued to be Hawaii's official anthem ever since annex ...

''.

The Hawaiian Islands, together with the distant Palmyra Island

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way between Hawaii a ...

and the Stewart Islands

Sikaiana (formerly called the Stewart Islands) is a small atoll NE of Malaita in Solomon Islands in the south Pacific Ocean. It is almost in length and its lagoon, known as Te Moana, is totally enclosed by the coral reef. Its total land s ...

, became the Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

, a United States organized incorporated territory, with a new government which was established on February 22, 1900. Sanford Dole was appointed the territory's first governor. The Iolani Palace served as the capitol building of the Hawaiian government until 1969.

See also

* Democratic Revolution of 1954 *''Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

'' – historical novel by James Michener has fictionalized account of the Overthrow in Chapter IV "From the Starving Village"

*Hawaiian sovereignty movement

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement ( haw, ke ea Hawaiʻi), is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to re-establish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii due to desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-gove ...

* Kalākaua Dynasty

*Paulet Affair

The Paulet affair, also known as British Hawaii, was the unofficial five-month 1843 occupation of the Hawaiian Islands by British naval officer Captain Lord George Paulet, of . It was ended by the arrival of American warships sent to defend Ha ...

*'' Unfamiliar Fishes'' by Sarah Vowell

Sarah Jane Vowell (born December 27, 1969) is an American author, journalist, essayist, social commentator and voice actress. She has written seven nonfiction books on American history and culture. She was a contributing editor for the radio pro ...

*United States involvement in regime change

Since the 19th century, the United States government has participated and interfered, both overtly and covertly, in the replacement of several foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government initiated actions for ...

References

Sources

* * * *External links

morganreport.org

Online images and transcriptions of the entire 1894 Morgan Report * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawaiian Kingdom, Overthrow Of the United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries Coups d'état and coup attempts in the United States 1890s coups d'état and coup attempts 1893 in Hawaii Conflicts in 1893 Battles and conflicts without fatalities January 1893 events United States involvement in regime change